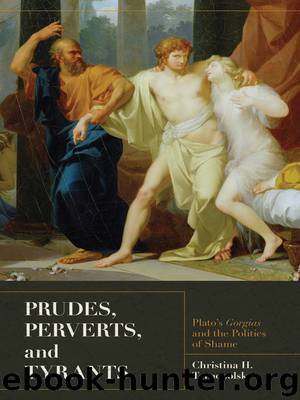

Prudes, Perverts, and Tyrants by Tarnopolsky Christina H

Author:Tarnopolsky, Christina H.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2014-04-11T04:00:00+00:00

* * *

1 See Dodds (1959), 30–34; and Kahn (1996), 52. As Dodds (1959, 32) puts it, “Apart from some short passages in the Laws, nowhere else in the dialogues has Plato told us directly what he thought of the institutions and achievements of his native city.” Dodds attributes this notion of a Platonic “Apology” to Friedrich Schleiermacher in the introduction to his translation of the dialogue. Plato’s own account of his disillusionment with Athenian politics in the wake of the restored democracy’s condemnation of Socrates is famously recorded in his Seventh Letter.

2 The idea that shame and free or frank speech are opposed for Plato is held by Allan Bloom (1968) who reads Plato as revealing the flaws in any democratic political system, and by Arlene Saxonhouse (2006) who reads Plato as a democratic thinker who is concerned to combat the imperialistic tendencies of democratic Athens. In his commentary on the Republic (which for him reveals the same Platonic teaching as the Gorgias), Bloom (1968, 336) argues that Thrasymachus’ blush reveals his shame and thus the fact that “he has no true freedom of mind, because he is attached to prestige, to the applause of the multitude and hence their thought.” Bloom’s interpretation associates shame with a conformist enslavement to convention in opposition to the truth. Similarly for Saxonhouse (2006, 76), “It is the philosophers’ stripping away that which we desire to hide from the gaze of others that brings on shame and it is the playwrights’ casting aside the shame that would inhibit their uncovering of the nature of our existence who can reveal, hē alētheia, that which is true. It is in this sense that shame opposes Socratic philosophy, for instance, in the activity dedicated to the pursuit of truth.” See also Saxonhouse (2006), 193, 212. Her interpretation associates shame (aidōs) with a kind of covering, and parrhēsia or shamelessness with a kind of uncovering or exposing. This, however, overlooks the fact that while the older term, aidōs, is linked to the notion of a covering mantle (Konstan, 2006, 296 n.17), the more classical and democratic term, aischunē, (especially in its connotations of dishonor or disgrace), is closer to the very notion of uncovering that she wants to link to parrhēsia and even to truth (alētheia). In this chapter I contest this opposition between shame and truthful speaking, and with it the suggestion by both Bloom and Saxonhouse that Socrates is shameless.

3 Cf. Bloom (1968), 336. According to Bloom, it is the philosopher alone who is truly shameless because his way of life involves questioning all laws and conventions. As I show in this book, while it is certainly true that flattering shame ties one to conventions and is at the heart of a dangerous kind of conformity, it is not true that all types of shame are slavishly linked to convention and opposed to the truth.

4 Kahn (1983), 115.

5 For Benardete (1991) and Stauffer (2006, 121, 182), the true philosopher would see beyond the noble and

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8968)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8363)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7319)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7104)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6785)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6594)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5752)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5744)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5495)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5174)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4434)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4299)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4257)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4241)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4237)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4235)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4120)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3987)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3950)